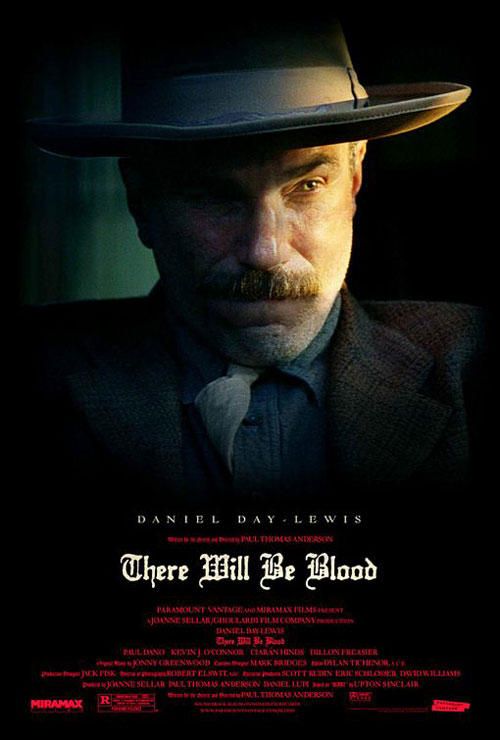

There will be blood

There Will Be Blood est un drame historique américain réalisé par Paul Thomas Anderson en 2007, sorti en France le 27 février 2008. Le film est tiré du roman Pétrole ! (Oil!) écrit par Upton Sinclair en 1927.

Fan de la musique du groupe Radiohead et particulièrement marqué par la performance de Jonny Greenwood dans la bande-originale de Bodysong (documentaire réalisé en 2003 par le Britannique Simon Pummel), Anderson fait appel à ce dernier pour travailler avec lui sur There Will Be Blood après avoir entendu son morceau Popcorn Superhet Receiver. Après quelques hésitations de la part de Greenwood rapidement rassuré par Anderson, Greenwood accepte de s’occuper de l’enregistrement de la bande-originale, travail qui l’occupera trois semaines dans les Studios Abbey Road à Londres.

[quote cite=”Jonny Greenwood / Nialler9 ‘An interview with Jonny Greenwood’, 21 juillet 2011″]The score for There Will Be Blood is brilliant piece of work. It’s a great example of music that heightens the narrative as well as adding to the unsettling tone of the film. What’s your process for scoring for film? Is it easier to set music to already established visuals and a narrative? What role does a director like Paul Thomas Anderson play in your scoring work?

Jonny: It’s easier having a reason to write music – something to hide behind. That music was written about those big landscapes, and the smaller chamber pieces were about the kid, HW. I had real luxury with that film: real soundtrack composers have made it clear to me that that was an easy ride: I could write what I wanted, and had the enthusiastic support of Paul Thomas Anderson: usually there are more than two people’s opinion involved in every decision, but on that film we were left to it. In the end, I wrote too much music, all about the story and the landscapes, and he even fitted some of the film to the music. Ridiculous. Shan’t happen again, they tell me…[/quote]

[quote cite=”Jonny Greenwood / Uncut, novembre 2012″]How did you get into writing soundtracks? And how does it differ from writing pop songs? As you can guess, I’m jealous of your new calling…

Matt Bellamy, Muse

It’s just a different way of collaborating with people – like being in a band with a director. And a bunch of images and stories instead of drummers and bass players. It’s fun! Don’t be jealous. Plus, you and I would only ever get to see the most pampered side of the job. Composers who do it properly all the time aren’t treated too well – on many films they’re ranked way below, say, make-up in order of importance, and not given much freedom to try things out. I was just offered a ï¬lm because they had to “let go†of their current composer and I think that happens a lot – in fact. I probably came close during the scoring for The Master. I kept adding jazz flute. Paul kept sending me pictures of Ron Burgundy.

How did you begin your collaboration with Paul Thomas Anderson? What attracted you to his ï¬lms?

Shane Rubano, Ithaca. NY

He found some bootleg recordings of some of my orchestral stuff. And tried it on a few early scenes for There Will Be Blood – then he asked for more. He’s enthusiastic about music, he came to the strings’ recording day in Abbey Road and we were both buzzing about being that close to an orchestra.

STAR QUESTION: Do you write “rock†songs as well as modern classical meltdowns like There Will Be Blood?

Stephen Malkmus

I’m hamstrung by having no singing ability at all – so aside from a few guitar chord sequences I can’t really write songs. As for classical stuff, I find it pretty pleasurable at the moment working on paper – it’s a bit like ï¬lm photography. Because there’s this long delay between having the idea and seeing if it comes out right. Weeks of work and it all comes down to one afternoon’s performance which is the first time you get to know what it sounds like.

What’s your opinion on the decision to decline you a well-deserved Academy Award nomination for There Will Be Blood just because you included some older compositions in it?

Allen Gallagher, Paisley

The bigger kick was just getting the job, and then that very happy day recording the strings in London – nothing was going to top that. Anyway, I have a Kermode Award, which I’m very proud of, even if it does look like a seven-year-old made it with plasticine and gold spray.[/quote]

[quote cite=”Uncut” cite=”avril 2011″]Greenwood’s music for films began in 2003 with Bodysong, a wordless documentary about human motion and activity with antecedents in films like Koyaanisqatsi.

“Jonny always wanted to go against the grain, mess with expectations,” recalls Bodysong’s director, Simon Pummell. “At one point he was looking into the possibilities of soundscapes of extinct languages. The way the percussion in the ‘Violence’ section slowly shifts into amore synchronised, obsessional beat-and moves from excitement to something oppressive, as the images escalate from brawling to genocidal brutality- is an example of the music really telling the story together with the images.”

He moved from art-house to mainstream theatres with Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood in 2007, with a harsh catgut accompaniment- “music about the characters and the landscape”, he says – that scaled the movie’s epic peaks and troughs with atonal introspection and wide-horizon scrape. Partly derived from a standalone commission he’d written for the BBC Concert Orchestra called ‘Popcorn Superhet Receiver’, it was a musical language of understatement.

“It’s recurring textures,” explains Robert Ziegler, who conducted the orchestra on both soundtrack recordings. “Certain clusters that he used, especially in There Will Be Blood, just nailed the quality of the film. And some of the new music he wrote, propulsive, rhythmic things, worked out wonderfully. He got that menace; on one of the most brilliant cues, “Open Spaces”, he played the Ondes Martenot [an eerie-sounding early electronic instrument] , and the whole conception of it was perfect. Those huge Texas landscapes, and it was just this little cue, but it lifted the whole film.”

I ask Greenwood whether he needs something visual as a starting point.

“Yeah,” he replies, “I enjoy having something to write the music for that’s of it not being that concrete, more an excuse to write music. My most exciting days ever are the morning of recording a quartet or an orchestra or a harp player, and knowing they’re coming, and setting up the stands and mics, and putting music out for them. And then after four hours it’s all over and you’ve got something.

“I’ve had a real soft ride. Traditionally film composers are way below the make-up people in the pecking order. It’s not seen as important, unless you find enthusiastic directors. And I’ve been lucky three times in a row.”

Is that excitement greater than coming out on stage in front of thousands at a Radiohead gig?

“Yeah, I think it is,” he says. “Because you’ve got weeks of preparation, and it’s just on paper and wondering what is going to happen. These great musicians are coming in, and you can hand them something that’s fairly lifeless and they can make it very musical. That’s been a big discovery for me you realise how much they put into it. . . they can make things sound musical even if it’s just a C major chord. It can sound far more exciting than you thought it was going to. It’s a big secret, but you don’t realise how much input comes from these people. ‘I can do this four or five different ways -which way would you like it?’ Or ‘You can get this kind of effect from the strings’, and so on.”

Robert Ziegler is in no doubt of Greenwood’s talents as a composer, citing Polish modernist Penderecki as an antecedent. “Obviously he’s got the same attraction to masses of sound and big clusters of orchestral sound. As a film composer you have to be careful not to ‘frighten the horses’ and the producers. .. ”

There Will Be Blood led directly to Greenwood’s next commission, as Tran Anh Hung used some of it as guide music on early cuts of Norwegian Wood. “When I saw There Will Be Blood,” says Hung, “I was completely seduced by Jonny’s music. It was a ‘new sound’ with a profoundness that I have not heard elsewhere in films. The emotions coming from his music were so… right, so mysterious and yet so obvious. No doubt for me that Jonny’s music would give a dark, deep beauty that Norwegian Wood needed.” Eventually Greenwood adapted another piece, ‘Doghouse’, for the finished film. ‘Doghouse’ is a triple concerto for violin, viola and cello, inspired by thoughts of Wally Stott’s scores for Scott Walker songs like “It’s Raining Today” and “Rosemary” languishing in the BBC library.[/quote]

[quote cite=”New York Times” cite=”9 mars 2012″]When I ask Greenwood, who’s almost pathologically self-deprecating in conversation, how his initial collaboration with Anderson came about, he says, “Well, that was Paul getting this bootleg recording of the orchestral concert, putting it against the film and deciding to use it, and then asking for more written like that. So, yeah.â€

Anderson tells the story a little differently. Even before he saw “Bodysong†at a film festival in Rotterdam, he says: “I knew there were arrangements that he had done within those Radiohead songs that obviously said he could do more than just play guitar in a band. And I thought, If the opportunity arises, I bet he could do something interesting on a film score. I was just sort of waiting for the opportunity.â€

As for what Greenwood said about “Blood,†Anderson laughs. “Yeah — he likes to say that. And I like that about him. That’ll never be beaten out of him. It’s a lot of head-scratching and, like, ‘Oh, I really don’t know if I can do this,’ or, ‘No, I can’t do this,’ or even, y’know, ‘I just shouldn’t do this.’ And then the next thing you know, you have an e-mail with like, 45 minutes of music in your in-box, and it’s all amazing and wildly different and terrific. That’s kind of him in a nutshell: ‘No, no. I really can’t. I don’t know how to do this.’ And then you get this huge platter of stuff.â€

Although “There Will Be Blood†will probably be remembered by people who never saw it as the source of the goofy Internet meme “I drink your milkshake†— the way pop culture has reduced “The Shining†to “Redrum†and Jack Nicholson saying “Here’s Johnny!†— “Blood†is one of the great movies of the 2000s, a work of historical fiction that presents the lust for petrochemical riches as a kind of American original sin, and a horror movie with a human monster at its center, the prospector-turned-oil-baron Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis). And Greenwood’s music is as crucial to the story as disco and “Sister Christian†were to “Boogie Nights.â€

The first 12 minutes of the movie have no dialogue — we watch Day-Lewis digging for silver in a filthy hole while the strings from “Popcorn Superhet†shriek and buzz menacingly, establishing right away that we’re looking at elemental evil. Yet Anderson says that when he screened the sequence for Greenwood without music, “he was jumping up and down, saying, ‘Oh, you’ve got to do it that way.’ †(The director eventually overruled his composer: “It really became a question of how European we wanted to get,†Anderson says.)

All told, Anderson estimates, Greenwood gave him about 90 minutes of new music for the movie. But because the final version of the score mixed that material with bits and pieces of “Popcorn†and a cut originally written for “Bodysong,†Greenwood’s work was ineligible for the Academy Award for Best Original Score, because of strict bylaws excluding “scores diluted by the use of tracked themes or other pre-existing music.†(The rule was also famously invoked when the Academy was forced to withdraw the composer Nino Rota’s nomination for “The Godfather†in 1972 upon learning that Rota had recycled some music he wrote 15 years earlier for an Italian film called “Fortunella.â€)

“Yeah, we got maneuvered out of the big one!†Anderson says. “I just wanted to see Jonny in a tuxedo. I would have paid top dollar for that.â€[/quote]

No Comment