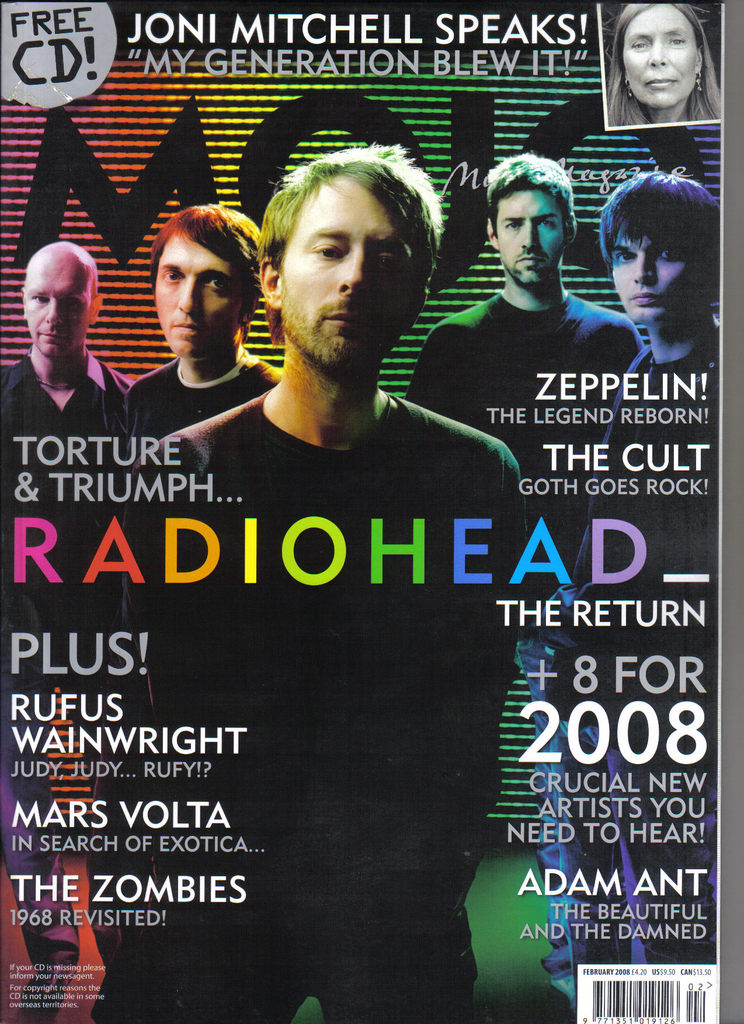

une interview dans MOJO

Rien de formidablement nouveau, mais on peut y lire une bonne rétrospective du travail du groupe depuis 4 ans. L’interview est très longue (et calme toute velléité de traduction…), mais assez intéressante pour qu’on s”y penche. Si vous faîtes l’effort, vous remarquerez une petite gaffe sur des paroles… On y trouve beaucoup de petites phrases très intéressantes.

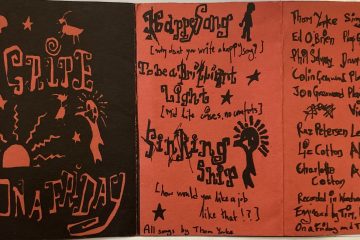

Les photos également sont très chouettes. (merci aux anglais qui ont pris la peine de scanner pour les diffuser ;), et à ateaseweb )

[quote cite=”Mojo”]

CHASING RAIN_BOWS

Four years in the making, In Rainbows is both tortured and triumphant… Here, for the first time, is the unexpurgated inside story of the album that nearly destroyed RADIOHEAD and gave the music industry a heart attack…

Words: MARK_PAYTRESS

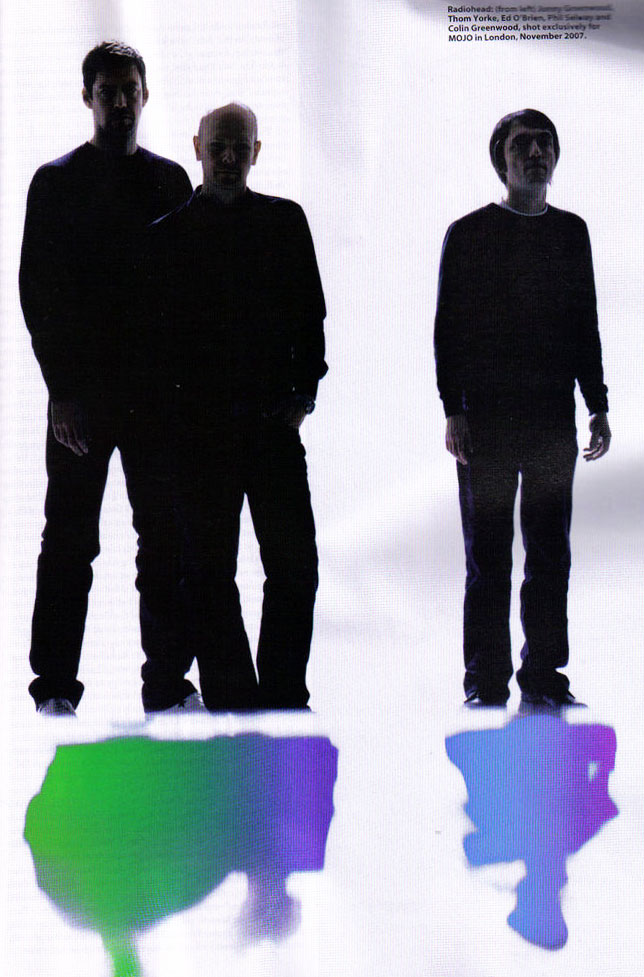

Pics: KEVIN_WESTENBERG

THEY WENT DEAF DURING THE SESSIONS. Imagined themselves as the Monty Python team with guitars. Battled rat poison and, more deadly still, their own desperately doubting ways. They thought it was all over (it wasn’t). Four studios, two producers, endless tweaks and retakes followed. But now, four years on from 2003’s Hail To The Thief, Radiohead are back with a record that even they themselves grudgingly admit has left them feeling “really excited and really proud”. That record is, of course, In Rainbows, MOJO’s album of 2007.

.jpg)

As well as shaking up the industry itself with its pay-what-you-want model, it’s an album that artfully distils the band’s very essence while at the same time avoiding the customary curses of cliche or complacency. And then, of course, there’s new eight new tracks on the bonus CD Discbox edition available exclusively via the band’s own website which paints an even more panoptic picture. A picture that will fully reveal itself during a week-long round of interviews with all five members of Radiohead as they unravel the titanic tale of their creative rebirth.

“I GUESS WE HAD HIGH EXPECTATIONS THIS TIME round,” shrugs Thom Yorke, in the quiet of a book-lined private room in The Old Parsonage Hotel (“The Old Parsnip,” jests Jonny Greenwood), an establishment with the ambience of a country house on the outskirts of Oxford city centre. In the relative tranquillity of the city Yorke still calls home, he exudes a warm glow, one that’s accentuated by the generous stubble of an incipient beard. He’s so relaxed, in fact, that he takes MOJO for a short tour of the city centre at the end of our interview. “Now that’s where several students were executed by the locals,” he says with a glint in his eye, while pointing at a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it bricked-out patch of Broad Street. Actually, the youthful-looking Yorke blends in perfectly here; all that’s missing is the college scarf.

Back at the Old Parsnip earlier, Yorke unleashes the first of several loud laughs that belie public perceptions of him as an arch, lemon-sucking miserablist. We’re talking about the difficult days of Hail To The Thief. “Yeah, we knew that was a lower part of the curve,” he says after a characteristic pause for thought, “and, yes, we knew we’d carry on. But it felt very much that the branch had become a twig – and that we could fall off the tree at any point!”

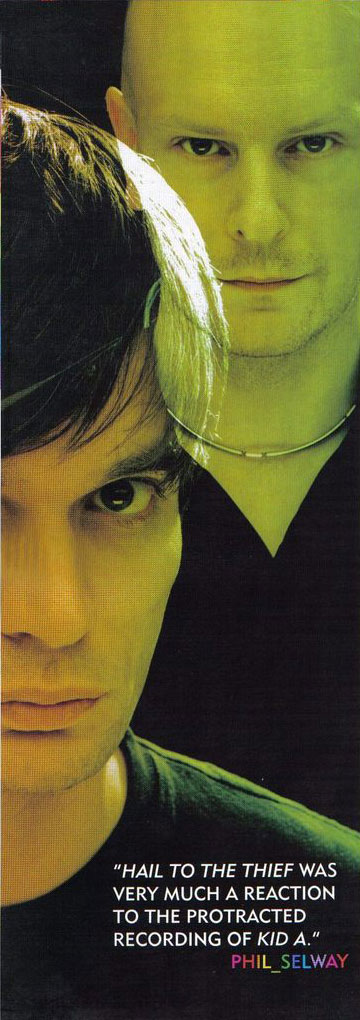

Yorke can laugh now, but on reflection the Hail To The Thief experience almost brought Radiohead to their knees. Indeed, no one could have foreseen the car crash ahead when, in July 2002, the band road-tested the material for two months before decamping to Los Angeles in September where they laid the basis of the album down in one two-week session. “It was very much a reaction to the protracted recording of Kid A,” says drummer Phil Selway, referring to the three years it took the band to follow-up 1997’s standard-bearer, OK Computer. “It was also a response to the excitement we’d rediscovered by playing the Kid A material live. We wanted to capture that on record.”

To some extent, it worked. Guitarist Ed O’Brien talked up the album’s “swagger” on its release, Yorke recalled how he wept when he first heard the playback to There There, and the band proved that they could do it without squirrelling themselves away for years and hiring a stately home for inspiration – as they’d done for both OK Computer and Kid A. But despite its intermittent brilliance (and There There does sound like a spellbinding peak of sorts) and initial commercial success, Hail To The Thief was a short-term compromise solution that quickly proved to be no solution at all.

“We should have pruned it down to 10 songs, then it would have been a really good record,” says O’Brien. “Working on In Rainbows, I was aware that we were making something that was really engaging, that moved people again. and I don’t think Hail To The Thief consistently did that. I think we lost people on a couple of tracks and it broke the spell of the record.”

Colin Greenwood knew as much from the start. “I didn’t want three or four songs on there, because I thought some of the ideas we were trying out weren’t completely finished.” Such as? “The Gloaming. We played it live and it was cool. My brother [Jonny] sampled each of the instruments on stage, cut them up then sent them back into the mix. It was so exciting, like a live DJ show, and Thom performed off of all of that. But it wasn’t the same in the studio. For me, Hail To The Thief was more of a holding process, really.”

SITTING IN THE QUIET OF “PROBABLY OXFORD’S first and last London-style private members’ club” above the QI bookshop, guitarist Jonny Greenwood, the most restless Radiohead member – “he has the patience of an insect!” says Yorke – also concedes that Hail To The Thief was a few songs too long. “We were trying to do what people said we were good at,” he admits. “But it was good for our heads. It was good for us to be doing a record that came out of playing live.”

SITTING IN THE QUIET OF “PROBABLY OXFORD’S first and last London-style private members’ club” above the QI bookshop, guitarist Jonny Greenwood, the most restless Radiohead member – “he has the patience of an insect!” says Yorke – also concedes that Hail To The Thief was a few songs too long. “We were trying to do what people said we were good at,” he admits. “But it was good for our heads. It was good for us to be doing a record that came out of playing live.”

If the suspicion that the record wasn’t quite up to their usual standard didn’t break them, then a year on the road touring Hail To The Thief very nearly did. After a short tour of Japan and Australia in April 2004, the band retreated back to their various young families. “It was definitely time to take a break,” says Phil Selway. “There was still a desire amongst us to make music, but also a realisation that other aspects of our lives were being neglected. And we’d come to the end of our contract [with EMI], which gives you a natural point to look back over at what you’ve achieved as a band.”

Any suggestion that this ‘natural’ break was a cover for a more ruinous rift within the group is rebuffed by O’Brien. The most relaxed band member in person, he is also the one least bound by what might be termed Radiohead-speak. “No, I didn’t think the band would collapse. I wasn’t scared. You know, if it all collapses, it’s only a fucking band.” But a livelihood, too. “Yeah, it’s a living, it’s a very nice living. But we’ve all got nice houses. We’re not gonna starve. There are always other things we can do. But I wasn’t ever worried about it. The good thing that came out of it was confronting things.

Confrontation they can do, but they don’t really do compliments. Mention Nick Kent’s claim in this magazine in 2001 that they were “the most important band in the world”, and they’ll pretend they haven’t heard what you’ve said. It is proof, if more is required, that the group consider themselves the best judges of their work… and, perhaps, of a little moth-eaten modesty. Wanna see Thom Yorke in fits? Float a rhetorical ‘top of your game’ across the table and watch his reaction. “Wait till you see the file of photos that comes with the record box,” he splutters. “Then ask yourself whether we look like we’re at the top of our game.” MOJO reminds him of a picture posted up on the group’s Dead Air Space blog that accompanied the October 1, 2007 announcement that the release of In Rainbows was imminent. In it, Thom, Ed and Colin [!] hold mugs of tea and look almost insanely happy. “OK, that was a good moment,” Yorke concedes. “They do happen.”

Good, often astonishing moments have dogged Radiohead during their 15-year recording career. The 1992 single, Creep, the stand-out on what was otherwise a fairly humdrum indie-rock debut, Pablo Honey, became such an alternative nation anthem that the band dropped it from their set. 1995’s The Bends marked a great leap forward, thanks to stronger material, more sophisticated arrangements and growing studio savvy. Next, OK Computer confirmed Radiohead’s standing, prompting – with some justification – all those “Pink Floyd for the ’90s” comparisons. Excepting Thom Yorke’s misguided early recourse to blond hair extensions, they were, after all, largely anonymous figures that appeared to shun the usual temptations of the rock’n’roll lifestyle in favour of a more considered, almost morbidly serious approach to their music. Oh, and let’s not forget Radiohead’s Oxford to the Floyd’s Cambridge.

Good, often astonishing moments have dogged Radiohead during their 15-year recording career. The 1992 single, Creep, the stand-out on what was otherwise a fairly humdrum indie-rock debut, Pablo Honey, became such an alternative nation anthem that the band dropped it from their set. 1995’s The Bends marked a great leap forward, thanks to stronger material, more sophisticated arrangements and growing studio savvy. Next, OK Computer confirmed Radiohead’s standing, prompting – with some justification – all those “Pink Floyd for the ’90s” comparisons. Excepting Thom Yorke’s misguided early recourse to blond hair extensions, they were, after all, largely anonymous figures that appeared to shun the usual temptations of the rock’n’roll lifestyle in favour of a more considered, almost morbidly serious approach to their music. Oh, and let’s not forget Radiohead’s Oxford to the Floyd’s Cambridge.

Although the genre has since been largely rehabilitated, the ‘prog’ accusation became a stick with which to beat the band, especially among the Britpop pack whose geezerish anthems grafted the sound of The Beatles’ Revolver onto the simple gratifications demanded by Loaded Man. Just as they’d raised their game after being accused of being “a pitifully lily-livered excuse for a rock’n’roll group” in their early days, Radiohead again reacted wildly, deflecting the “Is this the best record ever?” hype around OK Computer by a hard-left turn in search of a new direction. It took the best part of three years and resulted in two laptop rock albums, the stunningly taut Kid A (2000) and its troubled twin, Amnesiac (2001).

The spur for this defiant dive into electronica was Thom. It was mooted at the time that not everyone in the band was as fanatical as he was about the fractured beats and alienated textures that he had discovered after buying up the Warp Records catalogue. While Ed O’Brien looked in vain for melodies, Phil Selway wondered whether the laptop beats would put him out of a job. Hence, Hail To The Thief – a let’s-work-together bonding exercise, the effect of which, as we have seen, threatened the band’s unity more than at any other time in their 20-year tenure. Cue Thom’s solo album.

“YOU CAN’T GO ANYWHERE WITH THOM WITHout him having a laptop and headphones on,” says Jonny Greenwood. “It’s been like that for years, and he’s still doing it. We drove to London yesterday and he had his laptop out and his headphones on for the whole journey. That’s what he’s like. Always filling notebooks, too…”

While Radiohead are definitely A Band in the sense that all five musicians contribute greatly to the overall sound and character, it is Yorke who is very much first among equals. From the beginning, it’s mostly been his demos that form the basis for each Radiohead record, not least because he’s the proverbial creative – totally unable to switch off. He claims he’s been “training” to change all that. “But you’ll have to talk to my missus – sorry, it’s Rachel, she hates being called that – to see if that’s worked,” he smiles. “Yes, it’s true: I constantly have bits of paper in my pockets, backs of envelopes, notebooks. But, you know, 95 per cent of it doesn’t get used.”

Released in July 2006, Yorke’s solo record, The Eraser, provided an outlet for some of his excess creativity. Despite Thom’s twig analogy, there was, Radiohead insist, never a suggestion that he was abandoning the band. Now portrayed as an itch that needed scratching, The Eraser is a slow-burn melance of dislocated dance textures, piano-led moodsong topped with melodies that grow deliciously with every listen. “Great record, amazing singing,” enthuses Jonny Greenwood. “He had to get this stuff out, and everyone was happy that it was made. He’d go mad if every time he wrote a song it had to go through the Radiohead concensus. The combination of him, [producer] Nigel Godrich and a few months seemed to get it all unblocked.”

Yorke himself clearly appreciated the experience. “Actually, I did learn something from it,” he says. “It made me realise that all the stuff I do on laptops gets me excited because I can hear what I’m gonna do vocally. But unless I have a vocal in place, it’s a bit unfair to expect anybody else to understand what the fuck’s going on.” For example? “I was playing bits of Black Swan, six minutes of, er, mostly drivel, and Nigel’s like, ‘Bloody hell! I’m not interested in any of this.’ I said, I’ve been working on this for ages. It’s great. ‘No it’s not,’ he says. But as soon as I put the vocal on, he was like, ‘OK, now it makes sense.’ It reminded me just how important the voice is.”

And that realisation, as much as anything else, was to serve the group well during two long, cold winters and one long touring summer, in which time In Rainbows was painstakingly put together.

According to Jonny Greenwood, his own solo activities – two soundtracks, Bodysong (2003) and There Will Be Blood (2007), as well as being BBC composer in residence since 2004 – haven’t had anything like the impact on the band that Yorke’s renewed vocal awareness has. “Er, I don’t think I’ve done one [a solo album],” he shrugs. “I did music for a film but that’s different to cobbling together 50 minutes of music with your name on it and expecting people to listen to it. That doesn’t interest me at all. If I’ve brought anything new along, then I suppose I’m slightly less scared of asking violin players to do stuff than I was…” And a scary dub habit. “I spent six solid months listening to dub all day every day,” he says. “My wife still hasn’t forgiven me.”

The rest were publicly quieter but hardly immune from new influences. Ed O’Brien feasted on Rip It Up And Start Again, Simon Reynolds’ extensive survey of post-punk, and found it remarkably liberating. “That cemented a lot of the insecurities and boredom I was feeling about music. I realised, Hang on a sec, this is where I come from, and that’s the stuff that still moves me. It’s got melodies, it’s got pop, it’s trying to do things a bit differently – and you don’t have to work so hard at it…”

Colin Greenwood, meanwhile, continued to feed his eclectic musical interests, turning on to DJ Surgeon, encouraging fans to go out and catch Scouse screwballs Clinic, and learning a bunch of Macca and Motown ace James Jamerson basslines. Phil Selway joined Jonny Greenwood in the fictional band The Weird Sisters in Harry Potter And The Goblet Of Fire film. So far, so fragmented.

MID-FEBRUARY 2005: TWO YEARS AFTER FINISHing Hail To The Thief there, Radiohead regroup at their Oxfordshire recording studio. Initially, the prospects appeared favourable in terms of the music they set about making. Speaking the following month, Jonny Greenwood enthused about the “good songs” and the renewed hunger within the band. He also said that early rehearsals had been “fun”.

Ed O’Brien: “The moment Thom came in with the songs and the lyrics, it was the first time in a long while that I felt really engaged with the lyrics. I thought, These are great, these are moving me, these are lyrics written by somebody who is engaging with the stuff of life. That was exciting.” While no one admits to anything so simple as a gameplan, O’Brien probably expresses the band’s collective unconscious when he says, “I think ultimately we were looking for 10 or 11 songs, a really concise body of work, with no fat.”

Eight months later, on October 21, Thom Yorke posted an online bulletin on Dead Air Space, a new blog page at radiohead.com. It was the first of many, often fraught online updates he’d write over the next two years, that give a good indication of the agonising that went into the making of what became In Rainbows. Within two months, Yorke was back again, after another difficult two-week session. This time, his mood had darkened significantly. “We’re splitting up. It’s all shit. We’re washed up, finished,” he write.

“There was this sense,” admits O’Brien, “that we could finish this all tomorrow and so what. But it felt like it would be a shame to, particularly because when you got beyond all the shit and the bollcosk, the core of these songs were really good.”

“It was difficult to get back,” Yorke says, “and because things didn’t move forwards for ages and ages, it grew more and more tense. Things didn’t really ease until we started to feel we had something that had the emotional impact that we hoped the songs would have.”

Colin Greenwood: “I suppose we were paying the price for not taking the pain on Hail To The Thief. As this project progressed, we realised there are no short cuts to the process being exciting for us.”

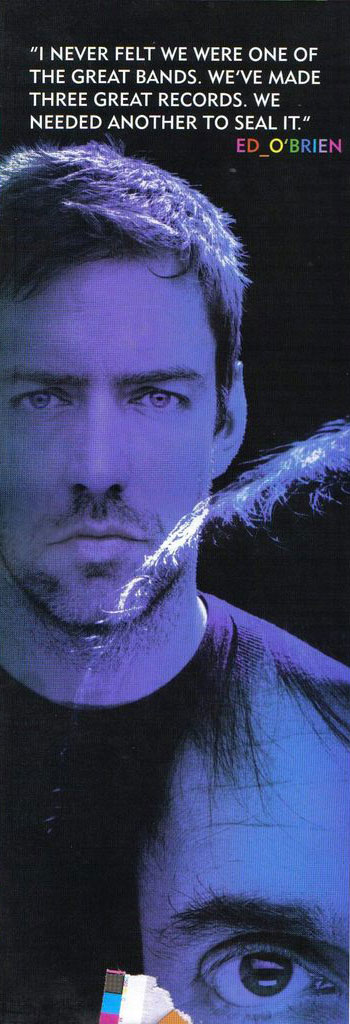

The initial high of February 2005 soon dispersed. Months of rehearsals, followed by the band’s own attempted to get some of the material down in a studio, gave way to debilitating – and characteristic – self-doubt. “There’s been such a crisis of self-confidence in making this record,” Colin Greenwood blurts out, his face etched with discomfort as he recalls the experience. “It’s been… really… terrible, you know.” This man is not joking. Like his brother Jonny, Greenwood thrives on the immediacy of a band playing together. His happiest memory of the entire process was “when we reheased at our old apple storage warehouse, a flattering room, which made everything sound big and rocky.” It didn’t last long. Much of the next two-and-a-half years were spent studio-bound.

In retrospect the problem appears both recurring and simple. Radiohead, a five-piece rock band, desire to make music that refuses to be bound by the limitations of their chosen genre. But movement away from the traditional into the unexpected often results in a frustrating process of distillation. “At the rehearsal room stage, things often sound very standard,” agrees Phil Selway. “The trick is to stick with that, because it does ultimately get you to a much better place. You must also be prepared to jettison the lot, too.”

So they did. In December 2005 Mark ‘Spike’ Stent was asked to work with the band in a bid to help them work through the material they’d recorded and stockpiled. “He listened to the stuff we’d been self-producing,” says O’Brien. “These weren’t demos, they’d been recorded in proper studios [in autumn 2005], and he said, ‘The sounds aren’t good enough.'”

Stent, known for mixing the likes of Bjork, U2 and Massive Attack, took over the production of sessions from February through to April 2006. Early versions of Nude, Bodysnatchers and Arpeggi were among the songs worked up, but he didn’t last long. “It never really took off,” says O’Brien. “But he was good for us because he galvanised the whole process,” adds Selway. “That had been missing up to that point.” Thom Yorke was far from happy, though. “I’ve been fucking tearing my hair out,” he wrote on the band’s blog in March. “Furiously writing, working out parts, cracking up.”

Despite their singer’s malaise, this first preparatory phase in the making of In Rainbows came to a head during May and June 2006, when the band toured Europe and the States, returning to the stage in August for two weeks of festival appearances, forcing them to concentrate on the material in hand. “That took us to the next phase,” says Selway, “because if you’re playing new songs live, you’re going to have to commit to some arrangements.”

MAY 1, 2006. AS THOM YORKE AND JONNY GREENwood performed an acoustic warm-up show at the Big Ask Live fundraiser for Friends Of The Earth at Koko in Camden Town, produced Nigel Godrich watched from the audience. Having worked with the band since 1004 and co-produced every album since OK Computer, Godrich had been the fall guy in the band’s initial attempt to break out of what Colin Greenwood calls “the safe zone”. His return to the fold took a further three months. By September 2006, says Selway, “We had prepared ourselves sufficiently for that whole working process to come back together.”

MAY 1, 2006. AS THOM YORKE AND JONNY GREENwood performed an acoustic warm-up show at the Big Ask Live fundraiser for Friends Of The Earth at Koko in Camden Town, produced Nigel Godrich watched from the audience. Having worked with the band since 1004 and co-produced every album since OK Computer, Godrich had been the fall guy in the band’s initial attempt to break out of what Colin Greenwood calls “the safe zone”. His return to the fold took a further three months. By September 2006, says Selway, “We had prepared ourselves sufficiently for that whole working process to come back together.”

“Thing came together when Nigel started working with us again,” nods Colin Greenwood, “because he was someone we knew when we had to be accountable to. Before then it was pie in the sky.”

All five members clearly hold Godrich in high esteem. “This is someone who, when he was six, built a mixing desk out of yoghurt pots and a black pen,” laughs Jonny Greenwood. “And he’s still like that.” Godrich’s patience, diligence and evidently obsessive interest in the music-making process make him an especially ideal partner for Thom Yorke. “I can keeping going with something for a very, very, very, very, very long time,†says Yorke, “until eventually I’ll realise I’ve been listening to the same two bars for hours. Nigel’s even more patient. We share that, and that’s one of the tensions, one of the dynamics within the band.â€

In a bid to bridge those tensions, and ease Godrich back into the fold after three years, in October 2006 band and co-producer decamped to a condemned Palladian country mansion, Tottenham House, outside Marlborough in Wiltshire. After all, decamping to a stately home worked for OK Computer and Kid A.

“It was literally an old country pile,†smiles Ed O’Brien, “huge and crumbling at the seams and with a Capability Brown front acreage that was astonishing. But the house had never properly functioned. It was expensive to maintain, and Stanley [Donwood], who does all our artworks, said the ley lines were not very forgiving.â€

During their three-week stay, the band occupied a couple of rooms, carefully avoided the rat pison, huddled together at nights in caravans, and recorded the basis of Jigsaw Falling Into Place and a ferocious take of Bodysnatchers, both of which ended up on the album. “You can definitely hear the atmosphere of the place on that,†says Thom Yorke. “We did loads of recording there, and three or four songs survived, but Bodysnatchers is the one live track on the record where we’re all playing together.â€

According to Colin Greenwood, the rumoured haunted ambience of Tottenham House imprinted itself into other parts of In Rainbows. “Nigel recorded the smudges and fingerprints of those rooms and put them back into the sound later,†he enthuses, “like the reverb on the House Of Cards vocal. His computer is like a rattle bag. He can pick out any sound, irrespective of where he recorded it, then map it on to a track we recorded somewhere else. Amazing.â€

A second pre-Christmas bonding session away from home, at the grand Halswell House outside Taunton in Somerset, proved less fruitful. “It was along way home and we missed out families,†says Colin Greenwood. “We didn’t achieve much there, so in the new year, we started to record in our own studio.â€

By then, several sessions has also taken place at Nigel Godrich’s Hospital Studio in London’s Covent Garden. There, in December 2006, Thom Yorke felt the first real glimmer of achievement. “We were looking for something that had a real effect on us, an emotional impact, and that happened when we were doing Videotape and I was semi kicked out of the studio for being a negative influence. Stanley and I came back a bit worse for wear at about 11 in the evening and Jonny and Nigel had done this stuff to it that reduced us both to tears. It completely blew my mind. They’d stripped all the nonsense away that I’d been piling onto it, and what was left was this quite pure sentiment.â€

By then, several sessions has also taken place at Nigel Godrich’s Hospital Studio in London’s Covent Garden. There, in December 2006, Thom Yorke felt the first real glimmer of achievement. “We were looking for something that had a real effect on us, an emotional impact, and that happened when we were doing Videotape and I was semi kicked out of the studio for being a negative influence. Stanley and I came back a bit worse for wear at about 11 in the evening and Jonny and Nigel had done this stuff to it that reduced us both to tears. It completely blew my mind. They’d stripped all the nonsense away that I’d been piling onto it, and what was left was this quite pure sentiment.â€

In complete contrast to the incendiary 21st century rock’n’roll of Bodysnatchers, Videotape is spellbinding in its morbid, haunting simplicity, and at its centre is Yorke’s extraordinary voice. It set the tone for much of In Rainbows.

For many, though, Yorke’s vocal on Nude, another key album cut, shines brightest. “Ten years ago, when we first had the song, I didn’t enjoy singing it because it was too feminine, too high.†He says. “It made me feel uncomfortable. Now I enjoy it exactly for that reason – because it is a bit uncomfortable, a bit out of my range, and it’s really difficult to do. And it brings something out in me…â€

Yorke’s new found vocal confidence might well be an outward manifestation of a change in his creative habits. The man who once complained that he was consumed by “mental chatter†has been working on himself. “I’m able to switch off now. Whereas five or six years ago, I absolutely couldn’t. I never switched off ever.” Mental chatter is, he claims, “to the detriment of work. One of the reasons this record has worked for me is that I’ve been trying to reduce how mcuh I work. The fact that I’m a dad too means I don’t spend an entire afternoon in front of a piano. Now I have to be a lot more focused when I work.” But, ever the doubter, he’s not entirely convinced by his own argument. “Hmm, I’m not sure that’s true. Maybe that’s all nonsense.”

This aspiration to locate a purity of expression is clearly evident in much of In Rainbows – from the spacious, stripped down production on several tracks to what seems to be more impressionistic, but obviously personalised lyrics. Yorke raises an eyebrow. “Really? Well, Reckoner is very much like that. It’s what sticks that I’m after and that happened a few times while making this. I try and do that thing where it’s sort of automatic, that whatever comes out comes out and try not to censor it too much.”

Yorke is certainly striving to find a new creative methodology. “The more you absorb yourself in the present tense, the more likely that what you write will be good,” he says. “Especially in this fucking town, where everybody’s sitting in front of their fesks for far too long, endlessly sweating over words that don’t ever get heard. People are obsessive in this city and work becomes an end in itself.” Given the three-year gestation period for In Rainbows, and Radiohead’s long-term ‘no pain, no gain’ attitude towards their work, his words come as a surprise. “There’s no point in writing notes and notes and notes and notes,” he continues, repeating words as he does habitually. “The polar opposite of that is Michael Stipe, who absorbs himself in other people and the life around him, and that’s where he gets his ideas. I’m not like that, but I absolutely understand why he does it. Neil Young claims he writes lyrics and doesn’t go back to them. If he does, he says, the worse they become. But my God, that’s scary. I mean, Faust Arp is the exact opposite of that, pages and pages and pages and pages and pages and pages until eventually, the good ones stick.”

Whatever his method, Yorke’s colleagues certainly believe their main man is on a roll. “I’m lucky because I’m working with a songwriter who I consider to be a peer of all those great soulful songwriters,” says Colin Greenwood. “And Thom’s singing, his phrasing, and his timing are just sublime. Listen to the way he sings around the beat on Nude and 15 Step. I don’t hear anyone who can do it like that, so instinctively, and in perfect takes.”

Yorke has not been alone in upping his game. Phil Selway and Colin Greenwood are surely the most inventive rhythm section working close to the rock mainstream. Multi-instrumentalist Jonny Greenwood brings a classically inspired serenity to several tracks, including celeste on Weird Fishes and the Discbox cut, Go Slowly, as well as sweeping string arrangements on Faust Arp and Arpeggi.

Typically, perhaps, Ed O’Brien is the only one who’ll actually admit that the project’s success was crucial to Radiohead’s survival. “One of my mantras throughout the recording was, This is the last time I’m doing this. I’ll never summon up the energy to do this again. So I’m going to put everything I can into it. I think everyone felt the same. This might be the last time. I really, really believed that.”

O’Brien also harboured a secret desire to confirm the band’s place in history. “I never felt we were one of the great bands, up there with The Smiths or R.E.M., you know. In my view, we’ve made three really great records, The Bends, OK Computer and Kid A. What we needed was another great record just to seal it.”

JANUARY 2007. AFTER SEEMINGLY CHASING THEIR OWN shadows for two years Radiohead repaired once again to their own Oxfordshire bolt hole. “Once we got back into our studio, we re-recorded a lot of the songs,” says Colin Greenwood. “But that was the period when it really came into its own.”

Despite struggling with certain rhythm tracks, one song that particularly benefited from an early 2007 refit was the In Rainbows opener, 15 Step. “The original version came out of bits assembled in the computer,” says Yorke, “and we were happy with that. Then we worked out how to play it live and the song ended up being something else again. We needed to push it as far as we possibly could. We’re always looked for ways to get out of our safe zone.”

As anyone who’s mouthed along to No Surprises or Karma Police knows, no one does ‘epic’ quite like Radiohead. Or, more accurately, like Radiohead used to. “That was a big issue on this record,” admits O’Brien. “Arpeggi, for example, is a song that’s obviously epic in scope. But every time we tried to do it, and fought against it being big, it didn’t work. The problem is that you’ve got to convince people that big doesn’t mean stadium. I think we do big music well; it’s kinda natural to us. But the problem with big music is the connotations that come with it, all that candles and stadium stuff. But epic is also about beauty, like a majestic view, and what we did on this record was to allow the songs to be epic when they have to be.”

In truth, Radiohead could have been the biggest stadium band of their generation. Yorke disagrees. “Actually, I can’t do it, and that’s why we’re not,” he says. “I’d have blown my brains out.” Yorke’s guarded approach to stardom is something which the rest of the band have used to their own benefit, allowing them to work in a mannger that involves a pronounced sense of self-regulation.

“Yeah, Thom is very wary of that and rightly so,” nods Ed. “It’s served us well. But equally you can stifle things if you don’t allow things to just let be. If you just let things evolve, there’ll always be a twist. What I like about this record are the times when we just let the song evolve and develop its own character.”

Eventually, as far as the troubled genesis of the album went, the evolution could go no further. A deadline was imposed for the start of July 2007. Colin Greenwood: “When we’d finished all the songs, we played them to our managers, and Chris [Hufford] said, It sounds like you’d just made this overwordy book. He was right.”

At a band meeting at Yorke’s house, in late summer, the production of one mastered 10-track CD was greeted with a huge sigh of relief. It took its In Rainbows title from a lyric on Reckoner – a song that had mutated entirely during the sessions. Each track on the album had to earn the approval of all five members. “I was just relieved that we didn’t muff up the arrangements, which is what you often feel when you finish a record,” says Jonny Greenwood. “And as it’s the first record where, a month later, I’m still listening to my six favourite songs, I think that’s a good sign.”

“The first time we all sat down and felt that it had worked was when we finalised the tracklisting and had the finished CD,” adds Phil Selway. “It was only at that point that we completely believed that we’d made the record that we wanted to.”

Indeed, the handful of tracks that didn’t make the final cut were not rejected for reasons of quality. “All those songs were in the running for the main album,” says Ed O’Brien, “but for one reason or another, they didn’t fit. In fact, each of us made strong cases for a few of those songs going on In Rainbows.” Jonny Greenwood was disappointed not to win the argument for Go Slowly, while the spine-rattling Last Flowers, Yorke’s trump card, was turned down as it had been taped for The Eraser and felt slightly alien in the In Rainbows context.

All the hard listening done to get this far had almost destroyed Colin Greenwood’s ears. “I used headphones incorrectly a couple of times and lost much of my hearing for two months,” he says. “That affected me profoundly. I thought I’d lose a lot of my top end, but it came back over time.” He wasn’t alone. “Thom had the same experience making this record. He’d use these same ‘closed’ headphones and they destroyed his top end. It’s terrible, it turns you off music.”

Compensation came in the form of the finished master. “I was really excited and proud,” says Yorke. “But at the same time, I desperately wanted to get the fuck away from it as fast as possible, because once I’ve played it all the way through and seen that finally it makes sense, that’s absolutely it for me. You only have a few days where you do, Yeah, we got something right, thank fuck for that. Then it’s time to do something new.”

That wasn’t long in coming. Right at the beginning of the album sessions, early in 2005, Radiohead knew they were out of contract with EMI, and were in no hurry to renew. The takeover of the company by Terra Firma, a private equity firm, in May 2007 sealed it.

“They just didn’t feel like they were in a very healthy position,” says Jonny Greenwood. “Every couple of years you’d hear, Oh, there’s a new person in charge. He used to work for a toothpaste company, or he used to run pensions. You’d think, What’s that got to do with music? It’s not like that at XL.” XL Recordings, part of the Beggars [Banquet] Group, secured the European rights to In Rainbows in the autumn, largely in the basis of Thom Yorke’s favourable experiences with the label when it handled The Eraser.

The idea of making In Rainbows available first via download had been germinating for some time, certainly as far back as a time when EMI were still hoping to re-sign the band. According to Phil Selway, the management company first suggested it. It obviously appealed to the band’s desire to make their material available more quickly, rather than groan through yet another three-month record company ‘lead time’. And it tickled Thom Yorke’s iconoclaustic tendencies. “It’s the art school thing. I have a fundamental distrust of, er, everything†he says laughing loudly. “I’d much prefer to kick the dust up.â€

And that, in a few words, is exactly what happened on October 10, 2007, now forever known as Radiohead Day. There was little warning. At midnight on September 30/October 1, Jonny Greenwood bashed out a short, simple message onto Dead Air Space from his kitchen at home.

“Hello everyone. Well, the new album is finished, and it’s coming out in 10 days. We’ve called it In Rainbows.

Love from us all.

Jonny.â€

A link led to the In Rainbows site, where forager soon discovered that they were being invited to name their own price for the download. Although Courtyard Management have yet to release firm statistics of their own, it has strongly refuted the results of one survey which suggested that 62 per cent of those who downloaded the album chose to pay nothing at all for it. Although they profess little knowledge-or even interest even-in the financial implications of the download approach, the band are fascinated by the art/commerce debate it’s stirred up. “We weren’t giving the record away,†says Colin Greenwood. “We were saying, What is it worth? Music is one of the only commodified art forms where when you walk into a store and records by Dylan, Roxette, Klaxons or The Hives are the same price. Does that mean they’re all as good as each other? Is there a way to say, by how much you pay, how good or bad something is? It’s good that the whole experience has got people asking those kind of questions.â€

“There was a big risk that if nobody gave any money at all, technically speaking we’d lose a fortune,” Yorke insists, “and I don’t just mean the recording costs but the cost of paying for the physical process of sending the downloads out. At 4p to 6p a time, that’s a lot of money when you add it up. Besides, we had no idea whether we’d get a load of shit for it.”

Instead, the reaction, which made front pages across the world, and prompted much debate on the business pages, was almost overwhelmingly positive – and hailed as a revolution in the way major bands sell their music. “It’s really not that radical,” Yorke reckons. “The only thing that was radical about it was that we were prepared to give something away that one might not normally consider in our position. But we never saw it as giving away. It has a worth regardless of whetehr you make people pay for it or not. As Chris [Hufford] said all along, this would have meant fuck all if the songs were rubbish.”

FOR YORKE, THE BIGGEST THRILL WAS MAKING A cultural impact “while sitting at home doing eff all. That’s cool, I’m down with that! But it’s not gonna happen very often. If we had our nuclear warhead, then I’m afraid that was it.”

As Jonny Greenwood’s simple announcement grew, virus-like, into an international story, it became obvious that In Rainbows was a taste of things to come. Record labels shuddered at the thought of other out-of-contract artists going the same route; fans found themselves thrilled at the prospect of downloading a new record knowing that hundreds of thousands of others were doing so at the same time. Radiohead Day was a remarkable event, but the band express no desire to go it alone and run their own record company. “The experiment was good, but we don’t wanna be spending the rest of our career in meetings discussing Portuguese shop displays,” says Jonny Greenwood. “It’s rehearsing and writing and being back in the studio where we’re happiest, really,” he says.

Neither do the band carry any guilt at cutting out the middleman to pocket the lion’s share of the money earned from the download. Of course, they’re acutely aware that the big money comes from touring and merchandising, and Yorke accepts that the Radiohead brand has been “elevated” by the entire episode. Ed O’Brien plays down the idea that Radiohead Day was ever intended as an “industry bashing event” and is more candid. “We’ve been putting money into our merchandise arm, W.A.S.T.E, for 10 years now and they’ve built it up into a really good little company. So we thought, Let’s make use of it.”

Hence Discbox, a lavish 12-inch square box-set of CD and vinyl editions of In Rainbows, an exclusive second disc containing eight new songs (see panel), photographs, artwork and lyrics – all in a book-stule package. Manufactured in a strictly limited run, Discbox sells for £40 (estimated sales to date: 80,000). But it’s not the only Radiohead box set on offer this winter – EMI have just released Radiohead, a similarly-priced package with all seven of the band’s Parlophone albums, complete with MP3s of the same material and a limited edition USB stick to carry then around on.

“Isn’t it nice?” says Thom Yorke, affecting his best Peter Cook voice. “No, I’m not really annoyed, and anyway there’s nothing we can do about it. If the choice is to dwell on that, or make a sign of the cross and walk away into the light, I’m gonna choose the latter.”

“It could have been far worse,” admits Jonny Greenwood, “like a cheesy greatest hits with the worst photo of Thom with big hair on the cover.” Well, that’s probably next Christmas, Jonny…

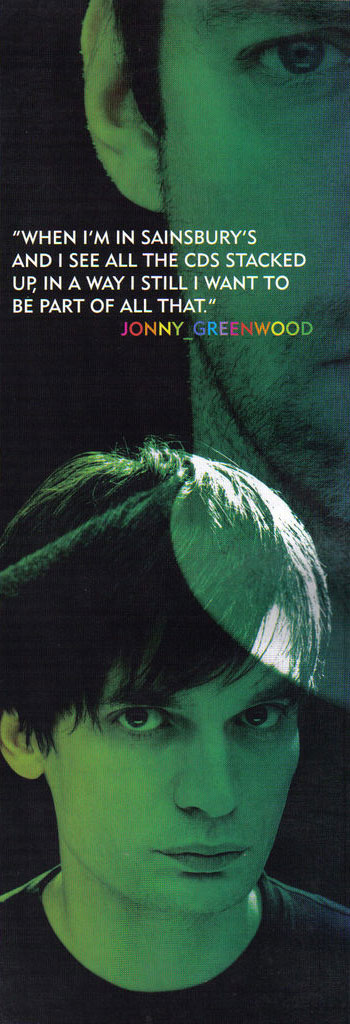

Not that Radiohead are opposed to the idea of seeing their work in the high street. “We’re really excited about the shop release of In Rainbows,” says Jonny Greenwood. “When I’m in Sainsbury’s and I see all the CDs stacked up, in a way I still want to be part of all that.” But will shops want a Radiohead album that’s been in free circulation for two months now? “That’s a good question. Once again, nobody knows. It feels like we’ve been in that situation a lot recently. And I like it that way.”

When it comes to hard and fast conclusions about the long-term ramifications of Radiohead Day, Yorke says, “I don’t think it changes things a great deal. I mean, everyone says that the structure of the music business is imploding, so that’s nothing to do with us. All we did essentially was give out a glorified leak date.”

And taken at least some of the control into their own hands. “Well, it would be nice if what we did was free up artists and musicians to think, I don’t have to sign my name in blood, maybe I can do this in a different way. But that’s about it. All we did was respond to a particular situation, and it was the logical thing to do, captain. We saw it as the best way to get the music we’d worked so hard on heard by the most people.”

OUR ALLOTED TIME IN THE OLD PARSNIP HAS LONG been exceeded, and the room needs to be vacated. “Are you rushing off?” Yorke says, before he offers to play Oxford City Guide. As one often chastised for his po-faced intensity, he’s more feet-on-the-ground than most song-and-dance men. He expresses concerns about the band’s tour later this summer. “That messes with my mind quite a bit from the environmental point of view,” he sighs, “but if you do it in bite-sized chunks, that might be all right.” If the campaigning Thom Yorke is less obviously present on the latest album – though House Of Cards and 4-Minute Warning on the second disc are informed by apocalyptic thoughts – his activism can be found all over Dead Air Space.

Oh, and one more thing – bearing in mind that one of the most startling images on In Rainbows involves Mephistopheles reaching up to snatch the singer away from the pearly gates at the commencement of Videotape – working in such a commercialised art form, does Thom Yorke really feel as if he’s sold some of his soul to the devil? “When I was at college, I was completely anti the idea of the tortured artist in the corner with his solitary canvas that then gets puts on the wall to be revered. I was absolutely into the idea that there’s no artefact at all, that there was just the reproduction, the aura of the original. I mean, you go to the Louvre, and there’s the Mona Lisa in a bloody shrine. What’s the point of that? The true art of the 20th century is art that’s reproduced. You don’t put it in a church or a gallery. You put it in a book or on a CD or on TV. So, no, I don’t think I’ve sold my soul at all.

“But I think it’s perfectly natural to be obsessed by the idea of selling out, or compromise, or losing it. I think that’s totally natural. I mean, you could see that happening to Kurt Cobain really fast. That’s because the place you write from is not the public cheesy-peezy person, it’s the one that’s left when all that crumbles. So it’s difficult, but I guess because of the nature of the people that we all are, no one’s ever really swallowed it whole.”

Really? Not ever? “Well, I think it’s human nature to want to get lost in it and believe that you’re wonderful. But I went the other way too fast and assumed that absolutely all of it – and we’re talking about the OK Computer era – was all bullshit, including me. I’d regularly stop midway through a song and think, I don’t mean a fucking word of this, I’m off. Which, I guess, is the polar opposite of someone like Marc Bolan. But it’s a product of the same thing. You’re always trying to deal with the fact that you’re a small crumbly piece of stuff when you write these songs, and maybe that’s why the songs are good. So you’re always taking one poison or another. Perhaps that’s what makes carrying on so hard. You make a record, you wake up and start writing something new, and everything crumbles again.”

[/quote]

1 Comment

[…] it down to 10 songs, then it would have been a really good record,†guitarist Ed O’Brien told Mojo in 2008. “I think we lost people on a couple of tracks and it broke the spell of the record.†[…]